From the Massachusetts Nurse Newsletter

July/August 2012 Edition

By Jeanine Hickey

Associate Director, Organizing

Short Pay! All Out! January 11, 1912! The call rings out in the textile mills in Lawrence, Mass. The textile workers leave the mills en mass and take to the streets of Lawrence. This mass exodus launched the great “Bread and Roses” strike of 1912 and marked the most significant rise in labor activism of that period.

Organizing and mobilizing for change would be seen as a huge catalyst in the eight-week strike and as we find in today’s work environment, an effective way to respond to rapidly changing working conditions. To understand why this is true, you need to know a little bit more about the strike in 1912 and how the workers organized themselves to improve wages and working conditions. In January of 1912 a law, voted earlier by the Massachusetts Legislature, went into effect cutting the work week from 56 hours to 54 hours. Now most of you would be saying “What is wrong with that?” Cutting hours should be a good thing but with that cut came a decrease in pay from the $8 a week they received. At that time the loss of two hours pay meant less to eat when workers were already struggling to feed their families.

Throughout the fall of 1911, the mill owners refused to meet with shop committees to discuss the up-coming cut in hours. This refusal made workers nervous and angry. For the workers, mostly European immigrants, women and children, this fight for “bread” quickly turned into a fight to address horrid building conditions, mistreatment by supervisors, and what we would call today “speed up” and quota systems. The workers, who spoke little English, had been holding meetings within their ethnic groups. Representatives from the groups met together to plan a strategy for the strike. They were being assisted by Local 20 of the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies).

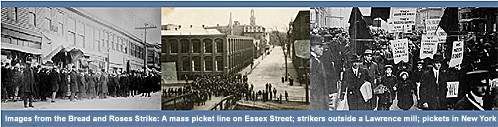

On Jan. 11, the call went out first from the Polish women of the Everett Mills. The strike was on and the next day thousands of workers walked out of the mills into the streets of Lawrence to be met by police and militia.

The workers’ committees would meet daily to coordinate activities and plan their strategies for what would prove to be a two-month strike. The strategy revolved around communication networks between strike leaders and the rank-and-file and community organizations which made sure workers’ families had enough food and access to health care. The committees rallied workers to participate in all aspects of the strike.

They built solidarity within the different ethnic neighborhoods; they used publicity effectively; and they raised funds to ensure that all families could survive the strike. These approaches were key to their organizing efforts and eventually the settlement of the strike. It was not an easy win. The workers faced opposition from the mill owners, city officials, police, the state militia and federal troops.

Officials banned parades and rallies, police and militia patrolled neighborhoods, and mill owners even hired someone to plant dynamite to discredit the workers. Police and militia resorted to violence, injuring workers and killing three of them.

The workers’ solidarity and creativity were the keys to the success of this strike. The “bosses” figured the employees would not be able to organize themselves because they were mostly women and immigrants from more than 25 ethnic groups who could not speak directly to each other. The strike would prove the bosses wrong.

Women played a critical role during the strike. They asked to lead the daily demonstrations and faced police brutality. In doing so they mobilized public opinion against the owners and the mayor. They were instrumental in organizing the evacuation of the strikers’ children to other cities to protect them from hunger and violence. The evacuation of the children turned out to be the most publicized event of the strike and became a turning point. When Congress and the public learned that the police were attacking mothers and their children at the train station to prevent them from leaving the city, they convened a hearing where they would learn of the low wages and impoverished living conditions of the workers.

After eight weeks and with some of the most brutal attacks against the workers of this period, the strike was settled. The workers would win a 15 percent wage increase with the lowest paid workers receiving the largest raises and the mill owners agreed to meet with grievance committees to improve other working conditions. The Lawrence strike was the catalyst that led to better pay and working conditions for thousands of other mill workers throughout New England.

What lessons can we learn from the Bread and Roses strike that we can use today in MNA/NNU bargaining units?

Communication is key to any mobilization or organizing effort. Getting to know your fellow co-workers should be the first step in the process. You should familiarize yourselves with your local union leadership. Communicate important information to the members of your bargaining unit. The most effective way of updating the members is face-to-face communications and walk throughs. Other methods of communications are newsletters, negotiation updates and electronic communications. The MNA staff assigned to your network can assist you in all of these communication tools. The mill workers all spoke a different language but understood that in order for them to be successful in the strike they would have to first organize themselves by ethnicity and then elect spokespeople to attend the larger strategy meetings. They understood the importance of communicating with their co-workers.

Organizational skills are important. Mapping your bargaining unit is an important tool to know where your members work, what shifts they work and the best way to get in touch with them. It is the most important tool needed for any member mobilization effort. The strikers knew that every worker was an important part of the strike and needed to be included in all aspects of the preparation and strategy. They also knew that there were different roles for each worker and each role was based on the strengths of the individuals. The MNA Division of Organizing can assist your bargaining unit with mapping.

Publicity and messaging. We know from experience that the right publicity and the right message by respected bedside nurses are of utmost importance in getting the message to the public. The Lawrence workers knew that messaging and publicity were very important as well. The publicity over the children being evacuated to other cities was the turning point of the strike. The MNA Division of Public Communications can assist your bargaining unit with crafting a message and a public relations strategy to effectively get your message across to the public.

Solidarity. When members are informed, prepared and united they are a formidable force with tremendous power to advocate for patients. The striking Lawrence workers were united in their resolve to improve conditions. It didn’t matter that they spoke several different languages or that the work force was predominately women. They were informed, prepared and united in their resolve to win better pay and working conditions.

Community outreach. This is another key component to any successful campaign or mobilization effort by MNA members. The MNA community organizers will assist bargaining unit members in reaching out to community groups, legislators, and other unions to gain support and solidarity for a campaign or issue being waged by the bargaining unit members. Having an informed community can lend tremendous credibility to the issue. The workers in 1912 spread the word to all of the ethnic neighborhoods and businesses, they rallied in all areas of the city, they held parades and they utilized other organized workers.

“