Massachusetts nurses filed more than 12,600 unsafe staffing reports from January 2022 to July 2023, showing patient safety risks that can be addressed by safe patient limits

Legislation requiring the DPH to create specific nurse-patient limits in hospital units would tackle years of deteriorating patient care quality and burnout that is driving nurses away from the bedside

Top nurse researcher Linda Aiken submits testimony in favor of Massachusetts safe patient limits, highlighting decades of studies supporting legislation

BOSTON, Mass – Nurses and advocates will testify before lawmakers on September 20 to the power of safe patient limits legislation to help solve years of declining hospital patient care quality and fix the underlying causes of the Commonwealth’s healthcare staffing crisis.

Nurses’ concerns about hospital patient care quality reached an all-time high this year, according to The State of Nursing in Massachusetts survey, with trends showing that understaffing and nurses not having enough time with patients are getting considerably worse. These problems are further documented by the more than 12,600 unsafe staffing reports filed by nurses across Massachusetts from January 2022 to June 2023, reports filed in real time that inform administrators of a staffing condition that “poses a serious threat to the safety and well-being of my patients.”

On September 20, nurses caring for patients in diverse hospital settings across Massachusetts, as well as elected officials and academic researchers, will make it abundantly clear that the only way to truly improve patient care and make frontline nursing sustainable as a profession is to set evidence-based limits on the number of patients a nurse cares for at one time.

“There is absolutely no question that limiting the number of patients a nurse cares for at one time is safer for patients and is the only solution to the nurse staffing crisis,” said Katie Murphy, a practicing ICU nurse, and President of the Massachusetts Nurses Association. “Until we ensure that nurses have safe working conditions with enforceable limits on the number of patients assigned to them, nurses will continue to flee the bedside by the thousands seeking a safer, more satisfying environment.”

Legislative Hearing Details

When: Wednesday, September 20, 2023, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Where: Room A-2, State House, Boston. Those who do not plan to testify but want to watch the public hearing may view the livestream under the Hearings & Events section of the legislative website.

What: Newly introduced patient safety legislation entitled “An Act Promoting Patient Safety and Equitable Access to Care” (S.1361/H.2196), sponsored by Sen. Lydia Edwards, D-Third Suffolk, and Rep. Natalie Higgins, D-4th Worcester.

The legislation features a different approach to developing nurse-patient limits in each unit of acute care hospitals than Question 1, the ballot question put forward by the MNA in 2018. The bill would empower DPH to hold public stakeholder hearings and promulgate regulations that establish specific limits on the number of patients a registered nurse shall be assigned to care for at one time.

The approach featured in the new MNA safe patient limits legislation is like that taken by California when it enacted a safe patient limits law in 1999 and implemented it in 2004. Research has shown that California’s law reduced nurse workloads, improved recruitment, and retention of nurses, and had a favorable impact on quality of care.

University of Pennsylvania Professor of Nursing and Sociology Linda H. Aiken, PhD, RN, FAAN, who has studied California’s nurse-patient limits and is the world’s preeminent researcher on the topic, submitted written testimony in support of the MNA legislation.

“There is a very large and rigorous research literature consisting of hundreds of studies and

multiple systematic reviews published in the most prestigious scientific journals in health care showing that the more patients nurses in hospitals care for each, the worse the outcomes are including preventable deaths, preventable hospital acquired infections, poor patient satisfaction and worse financial outcomes for hospitals resulting from longer patient stays, Medicare penalties for excess readmissions, and high nurse turnover that costs hospitals many millions of dollars every year,” Dr. Aiken wrote to the Massachusetts State Legislature. Click here for the full testimony.

Aiken pointed in her testimony to research on safe patient limits such as:

- Every 1 patient increase in hospital nurses’ patient workloads is associated with a 7% or greater increase in the odds that patients will die. Lancet, 2014.

- Today, patients in California hospitals receive on average 3 more hours of nursing care than hospitalized patients in other states. Dierkes et al., 2022.

- Research estimated that Pennsylvania and New Jersey, if staffed at levels mandated in California, would reduce surgical mortality by 13% annually. Aiken et al., 2010.

- Staffing in Californian safety net hospitals improved dramatically after the implementation of mandated minimum nurse staffing and there were no unintended negative consequences. McHugh et al.

- The gold standard for evaluating whether nurse ratio legislation improves health outcomes is from Queensland, Australia, by the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, and published in the top scientific journal, The Lancet. McHugh et al.

- It is the gold standard because the government of Queensland funded a prospective evaluation of the legislation before it was implemented and after two years.

- The Lancet paper documents that after implementation of the mandated minimum safe nurse staffing standards that thousands of hospital deaths were prevented annually, and millions of dollars were saved by reductions in average length of stay and averted hospital readmissions within 30 days of discharge.

“These studies document very large variations in nurse staffing levels across hospitals in the U.S. and within all states that have been studied. The public has no way of knowing that such large variations in nurse staffing exist and that their health and very life is threatened by chronic nurse understaffing in the majority of U.S. hospitals,” Aiken wrote to the Mass Legislature. “Chronic nurse understaffing predates the Covid-19 Pandemic and thus a

return to pre-Covid hospital nurse staffing will continue to imperil the public’s health.”

For more details on the supporting research, see this previous press release.

12,600+ UNSAFE STAFFING REPORTS AND CARE QUALITY DETERIORATING

Between January 2022 and June 2023, nurses filed at least 12,634 official unsafe staffing reports at hospitals across Massachusetts. These reports document to hospital management instances in which nurses were forced to take an excessive patient assignment that “poses a serious threat to the safety and well-being of my patients.”

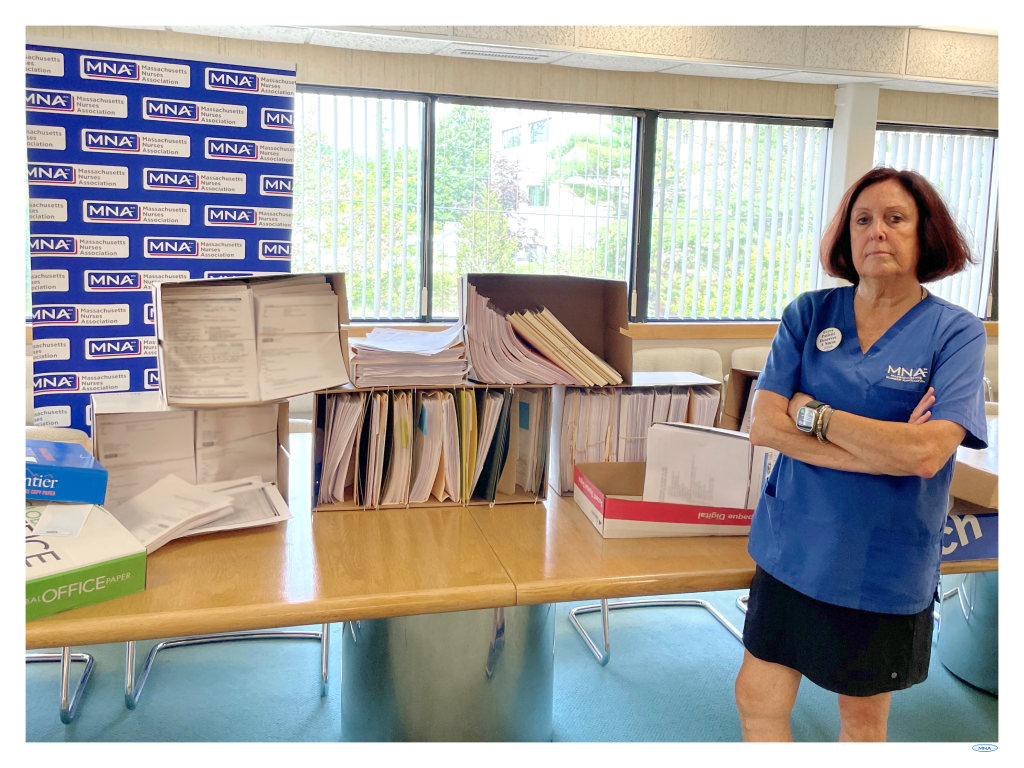

MNA President Katie Murphy, RN, standing in front of the unsafe staffing forms filed by nurses across Massachusetts between January 2022 and July 2023.

“Objection and Documentation of Unsafe Staffing” forms, as they are called, are used by nurses in all MNA-represented hospitals, which is 73% of the state’s acute care hospitals. They are a tool for nurses to document, in real time, any situation where they come on their shift and are given an assignment that is unsafe for their patients, which prevents them from delivering the quality care those patients require. Rarely, if ever, do hospital administrators take meaningful steps to address the problems identified by nurses in these reports.

The unsafe staffing reports dovetail with survey results showing that nurses are increasingly concerned about the quality of patient care in hospitals and that their biggest obstacle to providing quality care is understaffing and not having enough time with their patients.

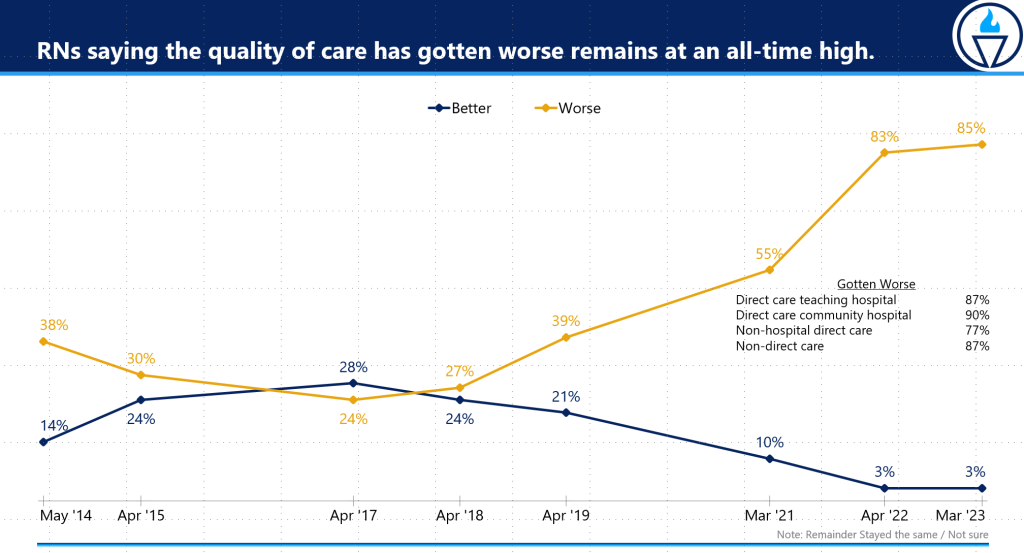

The “State of Nursing in Massachusetts” began tracking the quality of care in Massachusetts hospitals in 2014. The survey asks nurses about the direction of care quality over the previous two years. From 2014 to 2019, between 27% and 39% of nurses said care quality was getting worse. In March 2021, the first survey conducted after the onset of the pandemic, that number rose to 55%. In 2022, it spiked to 83% and then rose two more points to 85% this year. The percentage of nurses in direct care at hospitals who said this year care was getting worse was even higher.

- Nurses in direct care at a teaching hospital: 87% said care quality is getting worse.

- Nurses in direct care at a community hospital: 90% said care quality is getting worse.

Unsafe assignments have a clear negative impact on patients, with nurses in the survey describing the negative outcomes:

- 86% – have experienced a lack of time to properly comfort and assist patients and families.

- 80% – lack of time to educate patients and provide adequate discharge planning.

- 71% – patient re-admissions.

- 70% – complications or other problems.

- 59% – medical errors such as wrong medication.

- 58% – longer hospital stays.

- 49% – injury or harm.

- 23% – death of a patient.

LACK OF TIME WITH PATIENTS, POOR CONDITIONS DRIVING NURSES FROM THE BEDSIDE

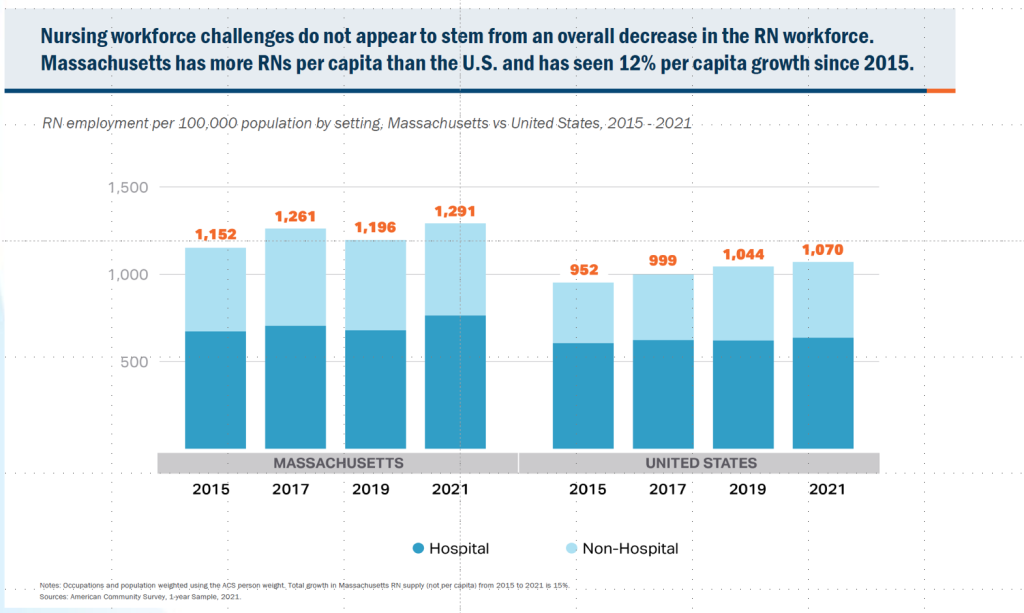

Massachusetts is experiencing a healthcare staffing crisis. Yet at the same time, there are tens of thousands of more nurses licensed in the state than a few years ago. The nursing education and training pipeline is getting more nurses into the profession, but they are increasingly turning away from bedside care because of unsafe patient assignments and the burnout and violence that comes with working in dangerous environments.

“To be clear, there is no shortage of nurses in Massachusetts, there is a shortage of nurses willing to continue working under the current conditions and staffing practices implemented by profit-driven hospital administrators,” MNA President Murphy said. “Now is the time for safe patient limits to help fix our broken healthcare system, address our staffing crisis and give the public a way to hold hospitals accountable for the quality of nursing care.”

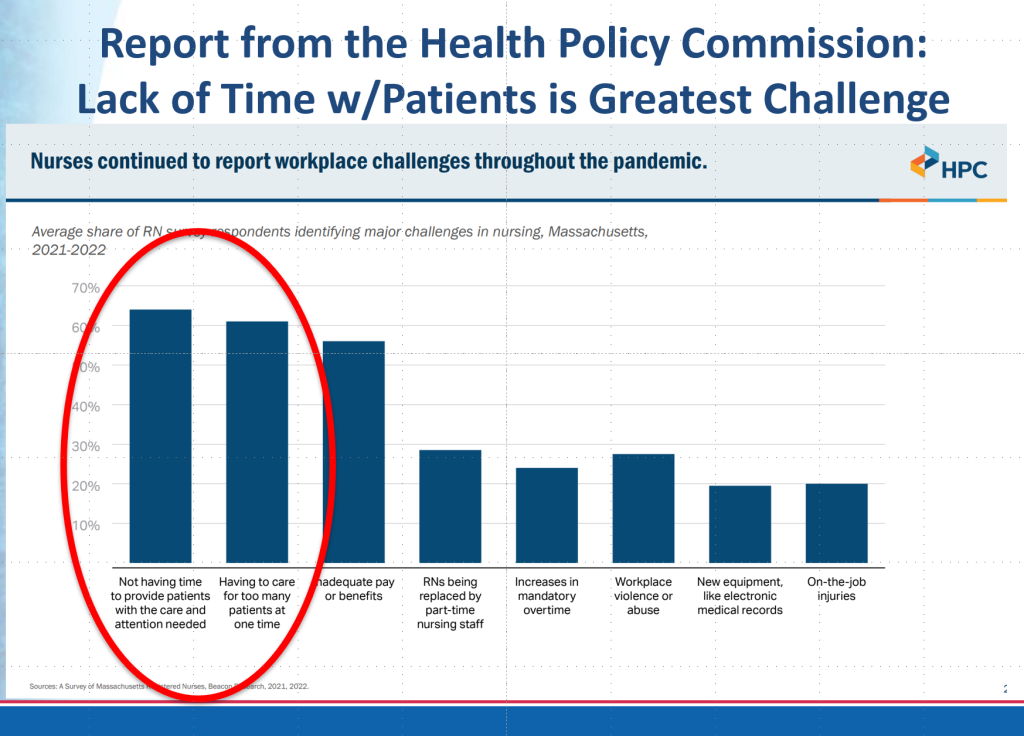

Historical survey data from “The State of Nursing in Massachusetts” shows that not having enough time with patients is a fundamental part of the nursing and care quality crisis, and that this problem has gotten worse. Nurses who said not having enough time with patients was a “major challenge:”

- 2017: 52%

- 2018: 65%

- 2019: 47%

- 2021: 61%

- 2022: 67%

- 2023: 72%

As a result, nurses are leaving hospitals, fleeing the bedside, retiring, seeking short-term contracts, or finding less intensive healthcare work. However, the state’s current nursing crisis is in no way attributable to any shortage in the supply of nurses.

Massachusetts recently ranked in the top five nationally for active licensed RNs per capita, graduates more than 4,000 new nurses each year from our nursing schools, and our nursing population increased by 24% over three years. According to an independent study of nursing supply by state, Massachusetts was one of only two states projected to have a surplus of nurses as of 2030. WBUR reported last year that the state Board of Registration in Nursing showed an increase in licensed registered nurses of nearly 29,000 from 2019 to 2022. And that was in addition to nearly 12,000 temporary/travel nurses licensed during the pandemic up until that point.

The Health Policy Commission recently completed a detailed study on the healthcare workforce in Massachusetts. The commission concluded, “the current nurse shortages reflect increasingly difficult work environments, not a lack of nurses.” The report included the fact that nearly 7 in 10 nurses don’t have enough time with their patients and that more than 6 in 10 have too many patients to care for at one time.

“Massachusetts has the nurses to staff our hospitals at safe and appropriate levels, but too many nurses are no longer willing to work in hospitals afraid for their patients, their licenses, and their own safety,” Murphy said. “By setting evidence-based limits on the number of patients assigned to a nurse at one time, we can finally implement the one solution we haven’t tried to address the underlying cause of why nurses are leaving the bedside and why patients cannot get the quality care they deserve.”

A NOTE ON COSTS

In 2018, the Health Policy Commission reported that staffing hospitals at the safe limits called for in the MNA’s ballot question would cost between $676 million and $949 million to implement. While the MNA disputes how that figure was determined, it is important to note that hospitals spent $1.5 billion on temporary nurse staffing alone in 2022. Had Massachusetts simply invested years ago in providing appropriate permanent nurse staffing levels, the data suggests we would not be in our current nursing crisis and would have gone into the COVID-19 pandemic better prepared.

In addition, safe patient limits have been shown to reduce costs in numerous studies. The researcher Linda Aiken and her colleagues have conducted outcomes evaluations of pending safe patient limits legislation in New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania. Aiken’s testimony notes, “The cost of adding additional nurses to meet the minimum staffing standards in pending legislation would be largely offset by millions of dollars of annual savings by reductions in average length of stay, reductions in Medicare readmissions penalties, and reductions in very expensive nurse turnover.”

Furthermore, a study conducted by Judith Shindul-Rothschild, PhD, RN, a nursing economist at Boston College and a leading researcher on RN staffing and patient care quality, found that hospital executives in 2018 grossly exaggerated the costs to implement safe patient limits. Utilizing real-time data from the Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association (MHA) and matching data comparing staffing levels and costs with the California hospital industry, Shindul-Rothschild determined that hospitals could remain profitable by shifting non-direct care and administrative costs to investments in bedside nursing.

“Based on my research findings, in my opinion, limits on the number of patients cared for by RNs improves the quality of nursing care and patient outcomes, especially in hospitals that assign RNs more patients than peer institutions,” Shindul-Rothschild wrote in her study.

“All too commonly, when hospitals face financial challenges, one of the first responses is to cut labor costs by cutting the numbers of RNs available to care for patients or replacing RNs with unlicensed personnel. Throughout my career, and in testimony over several decades in the Commonwealth, I have emphasized that to sustain quality and access to care in Massachusetts hospitals it is vital that we assure there are adequate numbers of registered nurses at the bedside.”

-###-

MassNurses.org │ Facebook.com/MassNurses │ Twitter.com/MassNurses │ Instagram.com/MassNurses

____________________________________________

Founded in 1903, the Massachusetts Nurses Association is the largest union of registered nurses in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Its 25,000 members advance the nursing profession by fostering high standards of nursing practice, promoting the economic and general welfare of nurses in the workplace, projecting a positive and realistic view of nursing, and by lobbying the Legislature and regulatory agencies on health care issues affecting nurses and the public.